The issue of digitizing artworks has been a well-established topic of discussion in the Czech cultural sphere. However, at the institutional level, the conditions for making digital data accessible and preserving it remain unresolved. You have been working on this issue for many years, having initiated, for example, the Open Collections project, which maps the digitization of cultural heritage in the Czech Republic. What led you to focus on the digitization of cultural and historical data?

The first key impulse was my dissertation, in which I explored computer vision in the interpretation of digitized artworks. The second was the COVID-19 pandemic when, in the spring of 2020, all museums suddenly closed, and I started wondering what was left of them. I began researching what Czech exhibition institutions were offering online, and it quickly became apparent—virtually nothing. Until then, most museums had perceived their digital presence merely as advertising for programs held in physical spaces. They provided hardly any online materials with value for the general public. At that time, together with Tereza Škvárová, we realized that we could focus on the only content that was somewhat available online—digitized collections. We wanted to conduct a simple statistical analysis of the number of digitized artworks accessible online, even if they were just scanned images with basic captions. That’s how our Open Collections project was born.

The pandemic undoubtedly forced museums to rethink their approach to digital content. At the same time, these events were accompanied by accelerated technological development and political-economic incentives for digital innovation. How has this transformation changed Czech cultural institutions over the past three years?

In one of my presentations on this topic, I showed two screenshots: the first displayed the homepage of the National Gallery in Prague’s website in spring 2020, and the second showed the same page a year later. From an external perspective, it looked like two completely different institutions—one site was trying to promote in-person programs, while the other presented a new podcast, art-related articles on the gallery’s blog, and teasers for online guided tours. Czech museums made significant progress in a short time, and today, they routinely explore ways to offer curated content in both physical and digital spaces, striving for a hybrid approach. Our survey for Open Collections revealed that in recent years, many museum professionals have begun to recognize the importance of digitization, and 78% of museums reported improved conditions for digitizing their collections.

However, I don't want to suggest that creating digital content is a substitute for physical museums. A museum experience consists of much more than just viewing objects. When I visit an exhibition at the National Museum, I go there with friends, I’m curious about the exhibition design, I absorb the atmosphere of the space, I enjoy the aura of original works, I want to buy a T-shirt featuring the exhibition’s visuals at the museum shop, or take my kids to the play area in the café. It’s a multi-layered experience tied to a physical location, and not everything can be transferred to the digital realm.

The physical museum experience has its unique and irreplaceable qualities. However, less is often said about the new experiences and opportunities the digital sphere can provide.

It’s important to distinguish between merely publishing digitized reproductions online—which I see as raw material for further processing—and creatively curated digital content for a target audience. If we focus on the raw material, meaning catalogues of collections and artworks, the crucial aspect is that by making them accessible, museums open the door for third parties to work with this data. Content creators are not limited to museums alone; publishers, e-learning platforms, film studios, and game developers can all benefit. For example, in my favorite video game series Assassin’s Creed, you can find recreations of historical settings, including real artifacts sourced from digitized museum collections. Game developers need databases of period-appropriate artistic artifacts to create virtual objects and environments. As a result, video games have become a new medium for engaging with cultural heritage. Making digitized materials accessible is a prerequisite for further applications. If these datasets remain locked away due to technical and legal barriers, they cannot be utilized for creative industries, research, or education.

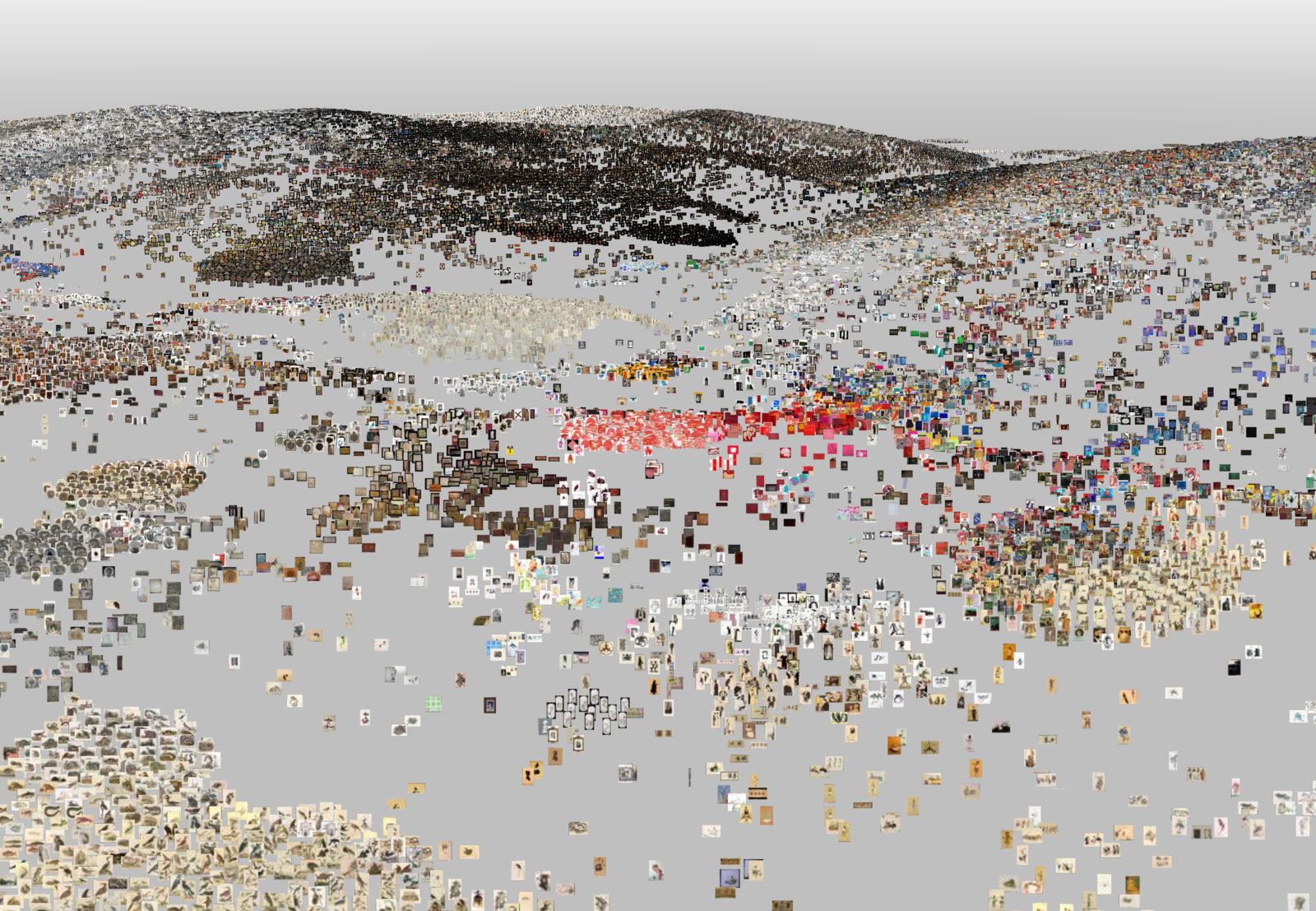

Interaktivní prostředí t-SNE Map umožňuje procházet databázi uměleckých děl spravovanou Google Arts & Culture Institutem. Jednotlivé artefakty jsou ve virtuální krajině seskupeny dle jejich formálních podobností. Čím více jsou si dvě díla podobná, tím blíže se na mapě nacházejí. Při sestavení mapy sledoval algoritmus „pouze“ podobu obrazů a nevyužíval žádná metadata či jiné dodatečné informace (autorství, datace apod.) Zdroj: Screenshot z experiments. withgoogle.com/t-sne-map

Museum data also has potential in the development of artificial intelligence. What specific applications do you see?

All AI models are data-driven. For example, generative models that create images from text prompts typically rely on datasets from platforms like Pinterest, DeviantArt, or Dribbble. These models are designed to mimic contemporary creative output. However, the same approach can be applied to historical data. You could, for instance, train a language model on books published in 19th-century Prague to create a chatbot that functions like a time machine—speaking in the language and mindset of the year 1900. The intersection of AI and cultural heritage presents new possibilities that are difficult to predict at this stage. However, one thing is clear: accessible historical and cultural data is a prerequisite for these innovations.

I know that integrating AI into museums is a topic close to your heart—not just from a theoretical standpoint, but also as a digital designer developing new digital tools. You're currently working on a museum visitor application. What is it about?

The app is called Cabinet of Wonders, and it’s a virtual guide that leverages generative AI and other technologies to enhance the museum experience. I believe that every museum visit can be inspiring and fun—it just requires the right kind of introduction to the exhibits that interest you personally. Ideally, that role is played by an enthusiastic curator or educator who knows you well. But since such people are in short supply, I’m developing an algorithm that can serve a similar function—suggesting personalized routes and highlighting engaging exhibits. The goal is for it to work across different museums.

What is currently the biggest barrier to making museum data accessible?

Copyright law. Imagine a collection of Czech modern art from the second half of the 20th century—none of the artists have been deceased for 70 years, meaning their works are not in the public domain. To make reproductions widely available, a museum would need permission from the artists or their heirs. In most cases, they don’t have such permission—partly because intellectual property rights weren’t always considered as important as they are today. Trying to resolve this retrospectively is challenging, sometimes even impossible. While tracking down copyright holders might still be feasible for a collection of modern Czech art, it becomes nearly impossible in fields like design, where authorship is often unclear. Museums are then faced with a difficult choice: make reproductions accessible and risk potential complaints, or keep the data locked away and inaccessible. This isn’t just a problem for museums—other institutions publishing historical materials face similar challenges. For example, Wikimedia Commons hosts many digital reproductions from both the present and the 19th century, but the mid-20th century is practically missing due to copyright concerns. That said, approximately 30% of the artworks in Czech museum collections fall into the public domain and can be digitized without legal obstacles.

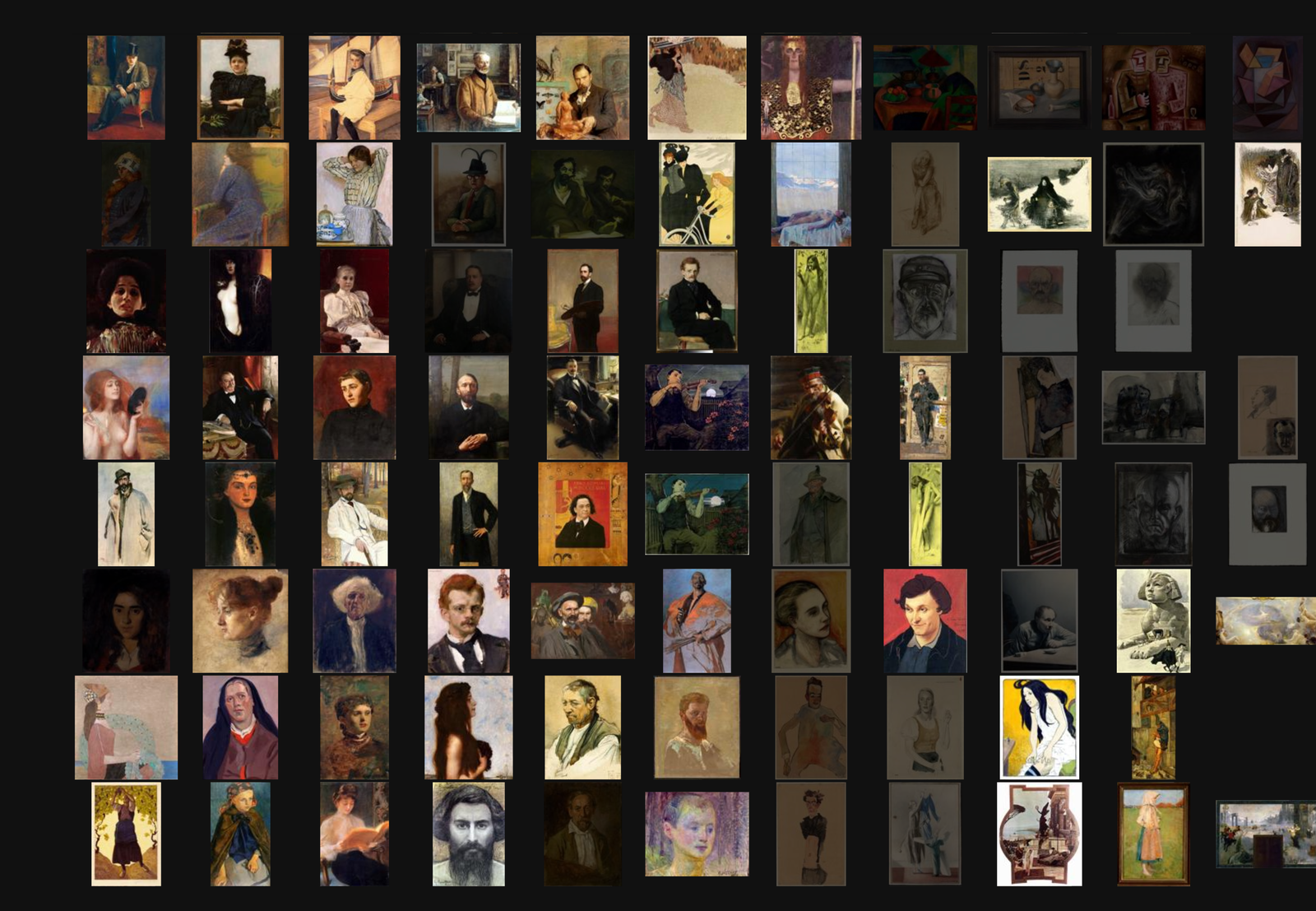

Detail vizualizace ukazující díla původních malířů Vídeňské secese. Foto: Lukáš Pilka

Your Open Collections project suggests that Czech museums are gradually—albeit very slowly—digitizing and opening up their collections. How accessible are these digitized artifacts through databases? Do museums use their own databases and catalogues, or are they striving for greater institutional integration?

There are several major international platforms, with Europeana being the primary one in Europe. It currently aggregates around 50 million digitized artifacts from various European collections—ranging from museums and galleries to libraries and film archives. Some Czech institutions, including those focused on fine arts, contribute to Europeana. Unfortunately, their participation is often only symbolic. For instance, the National Gallery has contributed exactly five works.

The same applies to the E-sbírky portal, which is intended to connect museum collections at the national level. When we tried to estimate the total size of Czech museum collections, we arrived at a figure of 25 million registered items in CES (the Central Collection Register of the Ministry of Culture). However, when I last checked E-sbírky, fewer than 250,000 items were available—just a tiny fraction. Accessing digitized materials through centralized databases also presents challenges: a universal interface does not suit all types of artifacts, and museum-specific context often gets lost. A good example of an alternative approach is MoMA, which used its photo archive and computer vision to link historical exhibition images with catalogue records of exhibited objects. This allows users to explore artworks in their historical exhibition context throughout the 20th century.

Managing digital data requires specialized technical infrastructure and expertise. How are Czech institutions coping with these new demands?

As far as I know, there is not a single Czech art museum with a dedicated, in-house team capable of managing digital databases and creating online catalogues or applications for presenting collections. Most of these services are outsourced to external companies, which is only a partial solution. What we desperately lack is a team of digital specialists embedded within museum institutions who can help define and implement a vision for their online presence.

In Slovakia, this role is filled by SNG Lab at the Slovak National Gallery, which provides digital services for most Slovak museums. I firmly believe that preserving and making digital cultural heritage accessible is one of the fundamental roles of museums today. The question, of course, is how to support museums in fulfilling this role, especially given their often limited resources and budgets.

How do you think museums can be supported in this regard? Should this be the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture, the Association of Museums and Galleries, or educational institutions that should train museum professionals more effectively?

Unfortunately, the Czech Association of Museums and Galleries does not have a dedicated committee for digitalization. At this moment, I doubt that this professional organization can take on an evangelizing role. The initiative is currently coming more from the Ministry of Culture and the Wikimedia Foundation.

Wikimedia offers educational programs for museum and archive professionals on how to publish digital reproductions on wiki platforms. And because Wikipedia has a high search ranking, this also serves as a way to promote museum collections.

Digitalization is often discussed in terms of making museum collections accessible to internet users regardless of their physical location. What about accessibility for disadvantaged groups? Does digitalization offer new opportunities in this regard?

Absolutely—and it’s not just about global accessibility. Anything that is digitized can be processed by additional digital tools. For example, a digitized text can be read aloud by a text-to-speech synthesizer, allowing blind individuals to access it audibly. Similar tools are emerging to describe visual materials as well. However, if material is not digitized, no third party can come along and create these accessible solutions.

Digitalization is a fundamental prerequisite for making art and cultural heritage available to people who previously had no access to it.

---

Lukáš Pilka is the founder and director of Cabinet of Wonders. He is also a digital designer, innovator, programmer, podcaster and enthusiast of old and new generative art. He completed his Ph.D. in 2022 focusing on the use of computer vision and neural networks to automatically classify artworks. Luke is also co-founder of the software company BlueGhost, creator of the experimental application DigitalCurator.art, and initiator of the Open Collections project.

Markéta Mansfieldová earned her master’s degree from Maastricht University in the Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management, and Education program. She further developed her thesis in a research project within the MRes Exhibition Studies program at Central Saint Martins, UAL in London. She has worked as a curator at Tate Britain, Lidice Gallery, etc. gallery, and the National Film Archive, where she contributed to the Video Archive research project.

The original interview was published in Artalk.